So, how does this magic happen? How do you start the creative process of coming up with a new game?

Blake: As developers who are primarily independent, this varies. Independently, we will both come up with games during game jams, and get prompts from other people, but we both also have a large backlog of our own ideas. Scrapeboard was started in a more unusual way.

We were involved in an installation at Babycastles called Store 2, which was a cross between a convenient store and a Goodwill, a store with a wide variety of food items made by different people, unique items made by artists, and other junk. We wanted to have a few very special items from celebrities, and we ended up acquiring a skateboard from Tony Hawk.

When we received it, we felt bad just selling it at the store and wanted to do something more interesting with this item.

Frank: I’ve had a backlog of ideas since I was a kid growing up playing video games. Sometimes, when I’m working on a game, the ideas evolve over time into something different. Other times, I’m inspired by other games or real-life occurrences.

How and from whom do you get your game design feedback?

Blake: We mostly get design feedback from players at events. Because Scrapeboard is a game that has a custom controller, it is harder for us to send out a digital copy and have people play at home to give feedback.

We have shown Scrapeboard at events primarily in New York, and several times in other states across the USA. For some of these events, we will invite other game developers to give in-depth feedback for us.

Often, the most helpful feedback is just watching people from off the street play. Sometimes we will be watching closely or from afar. We will see if it seems like they are confused about the controls, what modes they select, if they struggle with the difficulty, how long they play, and if they try again. Just watching is often much more helpful than verbal feedback, as sometimes people like to give unwanted suggestions, especially when they do not understand our design goals.

Frank: When it comes to something subjective like the art style of a game, I tend to ignore the feedback, knowing that a lot of the best graphics get a lot of pushback. I’m thinking of, for example, Wind Waker where a lot of players were turned off by the style, but it’s adored by so many others and contributed something special to the Zelda series.

It’s mostly a question of whether a player can take action, especially when I already know there’s a simple way to do it like a specific button they could be pressing and then prompting or guiding them into it.

Blake: We both have a pretty confident vision of what Scrapeboard is, so it is pretty easy to weed through the feedback, especially when it comes to the visual or emotional aesthetic.

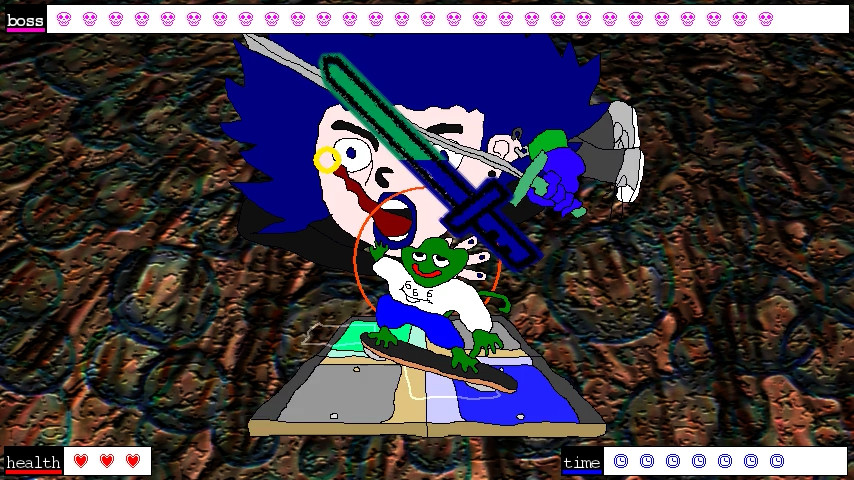

For example, Scrapeboard has a lo-fi art style that some people like and some other people do not really understand, especially since the crude art style seems to appeal to some fans of the game. However, if someone is confused about the clarity of what to do, we try to think of elegant ways to streamline the experience without sacrificing the charm of the game.

Do you keep iterating? Do you keep asking for feedback?

Blake: We frequently iterate on this game. Most times we show Scrapeboard in public, there are at least one or two small updates, whether it has something to do with our custom controller, the graphics, the level design, or difficulty.

While we do not always write down feedback, we are usually paying pretty close attention to the general vibe around the game. We also are always iterating on the context of this game. Is this a game that we show in an arcade? A bar? Larger game events? Outside? Do we get a DJ for a Scrapeboard event? Do we host tournaments for the game or leave it on free play? We are trying to narrow this down while still trying to keep things fresh and exciting.

Frank: For Scrapeboard, if there is a feature we’re working on we might have a playtesting session for the feature.

So for example, we were working on two types of skateboard controllers and wanted to see which worked better. During sessions, we ask for comments about the skateboard and how it feels to play. Once we got enough feedback, we stuck with one design and didn’t ask about the controller in other sessions.

In general, I mostly focus on features and don’t ask for general comments, but whenever someone shares their thoughts about the game, I take it as an indication of something relevant to the process of making the game.

Frank: There’s not much user data, it’s mostly in-person feedback and even non-verbal feedback based on watching people play that might be more specific to indie. When I see someone playing and I know they want to take an action and don’t know how to do it, I know I have to do something to clarify the interface or prompt the action in a more natural flow of the game.

Blake: Player feedback is super important for Scrapeboard, specifically because of its physical nature. It’s not a platformer that you use a controller with. Just standing on the board can be intimidating for players.

Some people think because it’s a skateboard, that it’s like skateboarding, which it isn’t. Some people think it’s like DDR (where players stand on a “dance platform” or stage and hit arrows with their feet to musical and visual cues), and that is also misleading. While it’s maybe similar to or inspired by these things, it’s super different.

We have to make sure that people can get used to it. While it’s a difficult game, and we enjoy that it is difficult, we also want it to be accessible to as many people as we can. However, we keep in mind that this game really isn’t for everyone. We take comfort in the spectacle of this game because it’s fun for people to even watch.

On approaching conflicting feedback

Frank: It depends. If there is a difference in difficulty, it might make sense to have separate difficulty levels. However, that’s an indication that even though two players may have different preferences, it might mean that something is causing confusion in a more general way. So, even getting a part of the game mentioned during the feedback process it’s a good indication to focus on it.

For example, some players were having trouble moving the board to different positions. Tutorializing some of these things helps even the playing field. Maybe it’s positive and negative and we would want to keep the positive feedback but it’s best that everyone feels the game is flowing naturally.

Blake: I try to think about what the root of the issue is for each issue. For example, some people would get the diagonal positions confused, some would not. We have also playtested Scrapeboard with different style boards, which is also often a split.

We try to think about what is the difference, or if it has to do with player skill. For example, there is a board that beginners like and one that experts like. We ended up not taking the beginner-friendly board to events, so beginners do not get used to using a worse board.

On improving the ways of gathering feedback from players

Frank: Since what I’ve found works best, I will try to have a goal regarding a feature that needs improving in mind before looking for feedback. I would start with paying attention to areas that need improvement, ones that might be confusing, and keep track of them across projects so I know which questions to ask.

Blake: Personally, I’d like to figure out how to make more money with Scrapeboard. This is especially difficult because of the unusual quality of the game. It’s difficult to figure out how to improve in this way because there are very few examples of things like this being profitable. However, we have started to make money from events and personal donations over the last couple of months.

Subscribe to our blog to read more stories about amazing creators from passionate professionals. Who knows? The next Hollow Knight’s gotta start somewhere.